Talking About Performance

I was nervous holding year-end performance reviews for the first time as a manager with direct reports. I had a few things working against me:

- My entire career as an individual contributor saw wholly positive reviews. I didn’t know how to receive negative reviews, let alone deliver them.

- I transitioned into management near the end of the fiscal year, meaning I didn’t have a strong grasp of each person’s body of work for the entire year.

- The team had no manager for 6 months prior so there was no one to consult about specific direct report performance.

With 17 direct reports, I had my fair share of awkwardness, lost sleep, and pain over the 2 week review period. Luckily, the experience was an excellent learning opportunity, and I have captured important notes about performance here.

Discuss Performance Routinely

The single biggest takeaway from my experience was to make performance a recurring topic of conversation.

For me, having 17 performance conversations is time consuming, so I now talk explicitly about performance during my monthly one-on-ones. I usually do some leg work before meeting to refamiliarize myself with the direct report’s work and to reflect on opportunities that align with any areas for improvement.

By having performance conversations frequently you accomplish a few things:

- You identify concerns early in the year and allow time for correction by you or by the direct report.

- If no concerns exist, you have a natural forum to thank and congratulate your team for good performance.

- You destigmatize the year-end performance review and make it far less stressful for everyone.

As an engineer I had always embraced fast feedback cycles but I never thought to apply them to managerial topics. Explicitly talking about performance is a natural extension of the feature branch testing, frequent production releases, and impromptu demos that we preach as a development team.

No one told me to have frequent performance conversations with direct reports when I became a manager. There was no document detailing things like this when I got the promotion. Instead, if was a messy trial-by-fire that resulted in disappointed employees and hurt feelings. However, embracing the lesson learned has made my team much stronger.

The Bell Curve does not Imply 50% are Poor Performers

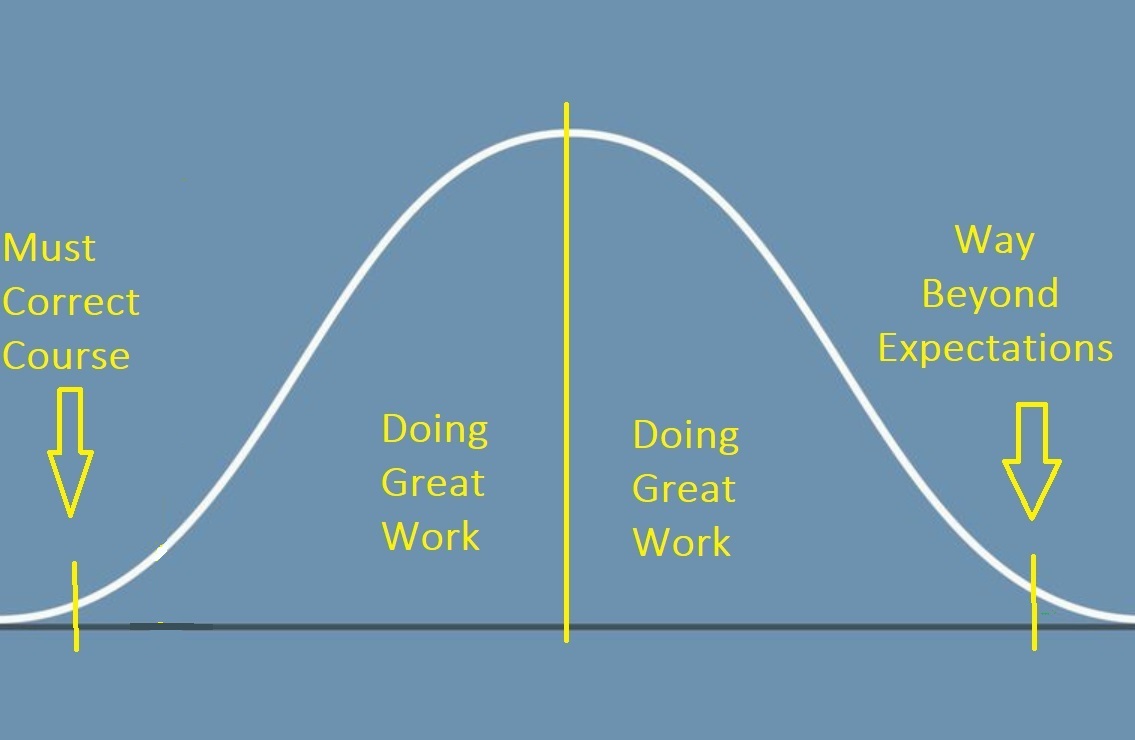

One assumption that I made when starting my first round of performance reviews was that the bell curve describing my individual direct report’s performance implied that 50% of my employees were “poor performers”.

Common sense and experience told me that this couldn’t be the case: my team was filled with motivated, intelligent engineers who enjoyed their jobs. But, ultimately, merit increases were to be allotted following overall performance, with higher performers earning more than lesser performers.

It was a fallacy on my part to think that “below average” meant “poor performer”. The definition of “average” is arbitrary and based on everyone else’s work, and does not accurately reflect the contributions that the individual team member makes.

While there certainly are direct reports who need to improve their performance, I can confidently say that 95% of the team are solid performers even if they would technically classify as 20th percentile.